H is for Happiness.

Most people think of happiness as an end result. However, it can actually be something that happens along the journey. Think of all the advice people give regarding happiness.

You must be happy with yourself before you can be happy with someone else.

Enjoy the small things.

Take time every day to be grateful.

Remember those who helped you and give back twice what you got.

Lots of good advice, but how often do people heed it? Complications wrought by the pursuit of happiness make good fodder for stories and for character development.

Is your character relatively happy with her life? If not, why not? What motivates her to be happy? Think about what a person needs to reach this state of being. It will vary between each one. If a character is not happy, and you offer her the means to be that way, to what ends will she go to achieve it? Is that the goal for this character, or will she find it on the way to something else?

A character may seek happiness by pursuing a specific thing. But maybe you could have her go after something she thinks will make her happy (like monetary success), only to find out that it is a complete lie, and she finds it by being honest with herself.

Image: Rosen Georgiev / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Some people enjoy being miserable all the time. How many of us have been suckered into helping a whiny friend or relative repeatedly, because nothing seems to get any better? They may use it to control others—making them miserable too, eliciting sympathy or even tangible goods and services from them.

Maybe they like the drama misery brings. Their lives are pretty good, but adversity brings attention. If they don’t have any, they manufacture some.

They may hide in misery. Fear of change, or of taking a risk at being happy and crashing to the ground in flames, they prefer to stay where they are. The devil you know is better than the devil you don’t, right?

The first major conflict in the story will affect your character’s happiness level. He may be pretty content at the start, but when he runs headlong into a huge change, he’ll have to choose a path. Will it be the safe one, or the dangerous one? Which will bring him closer to his goal, or help him achieve it? Will he be able to return to his previous content state, or will things change so much that he’ll have to accept a new normal?

@DrJohnWatson tweeted: Really just want a nice, quiet cuppa with my sweetheart and my best mate and—oh bloody hell. Bring on the danger. #addictedtoacertainlifestyle

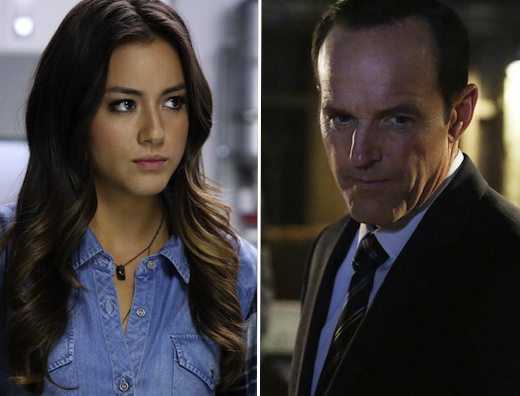

Image: primetime.unrealitytv.co.uk

(WARNING: Don’t click the image link if you haven’t seen Sherlock: Series 3 yet.)

If he’s miserable, try shoving something terrific at him and watch him squirm. Decide where you want your character to begin. Then you can mess with his life in all sorts of ways. Muwahaha, writing is fun!